NEZPERCE, IDAHO — Channa Henry had known who Bessie Blackeagle was since childhood, but they didn’t become close until adulthood.

That’s when they became "kind of inseparable," Henry said.

Their friendship continued after Henry joined the tribal police on the Nez Perce reservation in central Idaho, where the tribal member has spent almost her entire life, in 2017.

While on patrol, Henry had "a few run-ins" with the man who would become Blackeagle's boyfriend, Travis Ellenwood.��She was usually responding to reports of things like disorderly conduct, Henry said, but also for allegations of sexual assault against Ellenwood.

In one case, she said, Nez Perce Criminal Investigator Daniel Taylor — one of three tribal police employees later found by the Bureau of Indian Affairs to have engaged in misconduct — asked her to follow up on a report from Ellenwood’s then-girlfriend that she "had been raped and beat up."

People are also reading…

When Henry couldn’t track down the alleged victim, she said Taylor and another detective were "really nonchalant about it."

Channa Henry, one of Bessie Blackeagle’s closest friends, pictured at her home on Friday, Feb. 21 in on the Nez Perce Reservation. Henry is a former member of the Nez Perce Tribal Police.

Soon after, Henry said, she was again dispatched to a call from Ellenwood’s trailer. It came from his then-girlfriend, Jolene Cliffe. When Henry arrived with a backup officer from the local county, though, no one appeared to be there. She tried knocking on the door and calling Cliffe but "never got to catch up with her."

A day or so later, Henry said, Taylor located Cliffe, who acknowledged being intoxicated at the time she was allegedly assaulted, at the Orofino Hospital and interviewed her.

Some on the Nez Perce Reservation, including former law-enforcement employees, believe investigators’ failures to listen to the women who reported Travis Ellenwood’s alleged abuse allowed his violence to become deadly.��

"But he (Taylor) kind of played it down: 'Yeah, she's all on drugs, and she doesn't know what she's talking about. And she claimed that she was raped,'" Henry said, recalling what Taylor told her after the hospital interview. "He kind of made it seem like he didn't believe her. And I don't know, it just kind of made me sick to my stomach.

"I'm like, 'How can you not believe a victim? And why would you talk like that internally in the department about somebody about a case like that?' It wasn't a very open, objective opinion."

So when Bessie Blackeagle later told Henry she was dating Ellenwood, Henry said she warned her friend that Ellenwood was "dangerous."

She also said that being a law-enforcement officer meant she "had to be careful because I had confidentiality to maintain."

"I tried giving her a warning," Henry said. "I said, 'You know, I've had a few run-ins with him. I can't tell you very much, but I wouldn't date him.’ And she just brushed me off."

Then, almost exactly one year before her murder, Blackeagle called Henry and told her that "she just broke up with Travis, and had to get away," Henry said.

"So I went and picked her up in Kamiah," she continued, referring to a town on the east side of the Nez Perce Reservation, "and all she had was the clothes on her because she said she had to run out of the house."

As they drove away, Blackeagle removed her sunglasses, and Henry saw that she had red spots around her eyes that looked like petechiae, which is a common indicator of strangulation, as well as "markings on her arm, like scratches, and then kind of like dark marks, not really bruises, but dark marks around her neck."

"And that's when I kind of looked at her, and I said, 'Well, what happened?' And she said, 'Oh, nothing. We just got into a fight,’" Henry recalled. "And I said, 'No, what happened?' And it kind of went back and forth like that a couple times, and she just finally kind of got upset, and she said, 'I don't really remember, but we got into a fight, a physical fight.'

The Clearwater River runs through Kamiah, Idaho, on Saturday, Feb. 22.��

"I can't remember what she said," Henry continued, "but she downplayed what happened. And I got mad at her. I said, 'Well, how come you didn't report it to the police?'

"And then she got really upset with me," Henry added. "She threw her hands in the air, and she's like, 'I did.' She said, 'I called tribal police, and they didn't do anything about it. He wasn't arrested, and nobody followed up with me.'"

The next day at work, Henry said, she emailed her supervisors about it.

"I said, 'Hey, social services might want to go make contact with her. She's been a victim, and she did report this, so I was trying to make sure that procedures were done.' But after that, I didn't hear anything."

Kenton Beckstead, who acted as the head of the Nez Perce justice system while serving as Law and Order executive officer, said he knew of "several instances where cops and advocates had contacts with Bessie in the year leading up to her death."

In one, he said, police responded to a call and found Bessie with "marks on her neck and her butt was dirty from falling on her butt, which are pretty clear clues that she's been a victim of strangulation, which is a very serious crime, very high likelihood of death."

A map of the Nez Perce reservation on Saturday, Feb. 22 at the Nez Perce National Historical Park.

In fact, Beckstead said, "It's often the last thing (that happens) before the person does die — you catch the guy strangling her. But that wasn't caught on to by the investigating officer."

In a 2021 letter, Henry alleged that "Detective Taylor never sent the report" about Bessie Blackeagle "to the Prosecutor" and instead assigned an officer to "conduct follow-up with the victim, which was never done."

"And then next thing I heard from Bessie," Henry said, "was that she got back with him, and I remember I got mad at her again. I'm like, 'Why are you back with him?' And she got mad at me again and said, 'Well, nothing was done. He wasn't arrested. Nobody came and talked to me.'

"And she literally told me, she said, 'So I feel like I'm making a big deal out of nothing.' So then that's kind of why she went back to him."

That date is etched in Henry’s mind.

It was October 28, 2019. And it was the last day the two friends ever hung out.

"Because after that — after she got back together with him — he didn't like me having contact with her," Henry said.

Misconduct findings

Henry and Beckstead aren't alone in alleging that the tribal police’s failures had grave consequences, including Blackeagle’s death, a Lee Enterprises Public Service Journalism Team investigation shows.��

Numerous other former tribal police officers and tribal residents also contend the law hasn’t always been enforced adequately or fairly on the reservation. Some officers have been impeded in their ability to do their jobs, allowing some criminals to reoffend with devastating – and even deadly – outcomes, those critics allege.

Concerns about the tribal police are pervasive and long-standing. In May 2022, the Nez Tribe's General Council, which includes all enrolled Nez Perce citizens over age 18, gave the department a vote of no confidence.��

Henry, who spent years pushing within and outside the tribe for reform, introduced that resolution due to her concerns about "cases going unsolved and not prosecuted" as well as the department's conflicting and inconsistently applied policies, she said.��

A federal agency found some of the misconduct allegations against Nez Perce Tribal Police to be true.

Last year, the Bureau of Indian Affairs “sustained findings of misconduct by several former employees of the tribal police,” according to a memo obtained by Lee Enterprises Public Service Journalism team.

Those three former employees found to have engaged in misconduct were not just any employees. They were:

Taylor, who served as the department’s criminal investigator, a powerful position that involves leading investigations and working closely with the FBI on major crimes that are to be handled in the federal justice system, until 2024.

Leotis McCormack, who served as police captain until 2024.

Harold Scott, who served as police chief from 2016 until 2023.

The Lee Enterprises Public Service Journalism Team made a public-records request for the BIA’s complete investigative report in September, but the bureau had not provided it as of press time, nearly a year later.��

But the memo from Kenton Beckstead, the then-head of the tribe’s Law and Order Executive Office, said the misconduct identified by the BIA included “retaliation/reprisal, the willful or negligent making of an untruthful statement of any kind in any written or oral report pertaining to an officer’s official duties, and dereliction of duty.”

In an interview with Lee Enterprises, Beckstead described the contents of that BIA investigation, which resulted, he said, from "complaints of deficiencies in operations and investigations" within the Nez Perce police. Beckstead said the bureau's findings were focused on how Scott, Taylor and McCormack violated BIA policies through various actions.

‘Official response’

In response to questions, Rachel E. Wilson, the tribe’s communication manager, provided an “official response” on behalf of the Nez Perce Tribe.

Wilson wrote that the tribe is “dedicated to maintaining the highest level of law enforcement” and is “undergoing significant improvements” under Chief Mark Bensen, who took over the department in .��

“While acknowledging that past incidents may have involved missteps or misunderstandings,” Wilson added, “it is our priority to learn, evolve, and move forward with integrity and accountability. Due process has been followed in all cases to the best of our ability, and we continue to refine our practices in line with national standards.”

McCormack and Taylor did not respond to questions for this story, but Matthew Lovell, an attorney, replied on their behalf.��

Lovell said he is representing both men in “ongoing litigation with the Nez Perce Tribe and the Bureau of Indian Affairs” and declined to comment further.��

Efforts to reach Scott were not successful.��

A BIA spokesperson answered some questions about its procedures for investigating and overseeing tribal police but said the bureau “does not comment on how a tribe handles justice, as long as they follow their own rules and federal agreements.”

Flags fly outside the Nez Perce Tribal Executive Committee office on Saturday, Feb. 22, in Lapwai, Idaho.

‘I hope they’re OK’

Jenny Blackeagle had trained as a 911 dispatcher and kept a police "scanner going 24/7" at her home in Lapwai, which is the seat of the Nez Perce tribe, in late 2020.

And in the early hours of Oct. 31, 2020, she heard something that made her sit "straight up in bed": a 911 call about a woman screaming for help in the Kamiah area.

"I immediately sat up thinking, ‘Oh my gosh, Kamiah,’ because that's where my family is from. And so I was like, ‘Oh my gosh, I hope it's nobody that I know, and I hope they're OK,’" Jenny Blackeagle said.

As she kept listening, Jenny Blackeagle said she heard the dispatcher on duty alert a tribal officer to the report — and heard the officer say it was likely just "teenagers playing a prank" and that he wasn’t going to respond.

"And I just kept thinking, ‘Oh my God, how the hell does he decide this? Who is he to decide whether to go to a call or not? I remember being upset about it, and then I just laid back down and went to bed, went back to sleep," Jenny Blackeagle said.

Jenny Blackeagle looks out toward Travis Ellenwood’s former residence on Saturday, Feb. 22, in Kamiah, Idaho.

But late the next day, she recalled, her initial fears were realized.

The report wasn’t a teenage prank. It was a murder. And the victim was someone she knew: Bessie Blackeagle, her first cousin.

Jenny Blackeagle can’t help but wonder what might have happened if the officer had responded to the report of a woman screaming for help on the night Bessie Blackeagle died, instead of brushing it off until the next day.

But she thinks her cousin’s life could have been saved.

‘Probable cause’

Marcus Horton wasn’t supposed to go on patrol for the Nez Perce Tribal Police on that Halloween in 2020.

His wife and fellow patrol officer, Channa Henry, was on the schedule, but she wanted to take her son trick or treating, so Horton told her he’d take her shift.

As he hit the road in his patrol car, he saw an address pop on the screen of his mobile data computer that looked "familiar." He wondered if it was Bessie Blackeagle’s.

Then he opened the notes from a call that had come in from Ellenwood at 5:30 p.m., in which he reported that his girlfriend wasn’t breathing.

When he arrived, Horton found a sergeant from his department interviewing Ellenwood.

Marcus Horton lifts up his child on Friday, Feb. 21, on the Nez Perce Reservation.��

"He was talking to him, and I remember hearing the washer and dryer going," Horton said, "but at the time, I didn't think much of it."

Then he went down the hall, to the back of the trailer and found his wife’s best friend dead.

"I get my flashlight out, and I'm looking at her and I'm starting to see ligature marks show up on her neck," he said. "Pull my phone out of my pocket, and I called Dan Taylor. ‘Something's wrong. You need to get down here. This ain't right.’"

After Taylor came, the FBI arrived, as murder is among the "major crimes" that the federal justice system handles on tribal land.

After Horton was released from the scene, about 2:30 a.m., he "pulled over just to take a breath and think about things. And all of a sudden I hear him. I hear Dan Taylor say (Ellenwood) is clear, and he's taking the subject — I'll never forget that radio call — back home."

While Horton was a patrol officer and not involved in interviewing Ellenwood or investigating Bessie Blackeagle’s death, what he had seen — the ligature marks that indicated strangulation, the unusual way she was positioned on the bed, signs that he was cleaning up the crime scene — suggested Ellenwood could have been arrested.

And evidence he heard about later, including defensive wounds identified on Ellenwood, meant investigators "had probable cause to arrest him right then and there," Horton said.

But Ellenwood wasn’t arrested. For 10 days, he remained free, according to Horton, Henry, Jenny Blackeagle and others.

In the meantime, Jenny Blackeagle and others said, Ellenwood had a "bonfire every night up on his property."

"And we assume he was burning evidence," Jenny Blackeagle added. "We don't know what he was burning, but he was burning something."

Jenny Blackeagle visits Bessie Blackeagle’s grave on Saturday, Feb. 22, on the Nez Perce Reservation in Idaho. Blackeagle said she was awake in the early hours of Oct. 31, 2020, when the initial call about her family member Bessie Blackeagle came over her police scanner.

‘It affects all of us’

The delay in Ellenwood’s arrest only compounded the incalculable feeling of loss that was felt not only within the Blackeagle family but within the Nez Perce tribe more broadly, Jenny Blackeagle said.

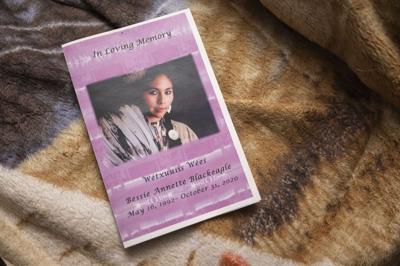

Bessie "was raised to respect the culture, be part of the culture, and speak the language," Jenny Blackeagle said. From an unusually young age, she said, Bessie was a fluent speaker of Nimiipuu, the language of the Nimiipuu people who comprise the Nez Perce Tribe. At the time of her death, Bessie was 28.

"So when we lose somebody that has that extent of knowledge, it impacts all of us," Blackeagle said. "And especially as young as she was, she was still able to reach down to the generations below her and able to have that relationship with them and teach them along the way. So it was a huge loss."

It was a loss, Jenny Blackeagle said, that "sets us back years" in the quest to "recover" a tribal culture that was severely damaged as the federal government confined the tribe to a reservation, occupied their historical land base, broke their treaties, massacred women and children and fractured the small piece of the land Nimiipuu were allowed. Today, the tribe’s 3,500 citizens own only about 13% of their 750,000-acre reservation.

"She should have become a grandmother and shared that knowledge," Jenny Blackeagle said of her cousin. "She had grandparent teachings. She had phenomenal knowledge. And when we lose our elders, and when we lose people who have the knowledge and the language, it affects all of us."

‘Brushed off and disposed of’

On Nov. 10, 2020, a federal grand jury indicted Ellenwood on a charge of strangulation.

In June 2021, Ellenwood was charged with murder for killing Blackeagle "by beating her and strangling her." He pleaded guilty to second-degree murder four months later.

Efforts to reach Ellenwood in the Federal Correctional Institution in Englewood, Colorado, were unsuccessful. But David Partovi, who served as Ellenwood’s defense attorney, said his client maintained his innocence.

"Travis just woke up next to his dead girlfriend," Partovi said. "She had pretty clearly been assaulted — very clearly had been assaulted, really bad. But it didn't look like it was bad enough to kill her, and yet she was dead. So I think the autopsy concluded that there was blunt force trauma to her head, and there was."

Partovi

"But that case always baffled me," Partovi continued. "He (Ellenwood) claimed to not have any memory of it, although he did say some things that were going to be difficult to get around to the FBI.

"And so my calculation on that case was, ‘Look, Travis, you were the only one present capable of doing this. We don't have any evidence that somebody else did it. And if you go to trial, you're probably going to trial against first degree. The consequence for that is mandatory life, you know.’ And he just decided, ‘OK, fine, I'll plead guilty.’"

While Ellenwood was sentenced to nearly 20 years in federal prison, Jenny Blackeagle thinks he deserved a harsher punishment.

"I wanted it to go to trial, because in a trial, he would have gotten life for everything that he had done to her," Jenny Blackeagle said. "Her body was, head to toe, black and blue — absolutely black and blue. And then they would have had to take in consideration everybody else's witnessing of her bruises, witnessing the abuse."

But the judge who sentenced Ellenwood did consider the experience of at least one of Ellenwood’s alleged victims.

In a victim impact statement, Jolene Cliffe, Ellenwood's girlfriend previous to Bessie Blackeagle, addressed Ellenwood directly, describing the "trauma and pain" that came from his vicious abuse — and from being ignored by police when she tried to report it.

"I reported crimes committed against me, very similar ones to the ones that you are currently incarcerated for, and they were not taken seriously, because I was an alcoholic," she wrote.

"A person could almost go so far as to say there was abuse in the aftermath of what took place," Cliffe added. "I felt brushed off and disposed of."

Jenny Blackeagle and Henry, too, say that police investigators’ failures to listen to the women who reported Ellenwood’s alleged abuse allowed his violence to become deadly.

Henry believes reports about Ellenwood’s violence were "handled totally wrong," and Blackeagle "absolutely 100%" agrees.

"They had a whole year to prevent the murder from happening," Jenny Blackeagle said. "The murder could have been prevented had the first initial call (from Bessie) in 2019 been answered and dealt with in a way that it should have been dealt with."

"But we'll never know," she added.

Next: Reform attempts after Bessie Blackeagle's death face 'tremendous pushback.'